Worldly Wisdom: 5 Lessons from Charlie Munger

Dear friends,

Welcome to another issue of Plutarch, the leadership newsletter for aspiring leaders. There has been a name change to my newsletter because I want to pay tribute to one of the greatest biographers of all time, Plutarch.

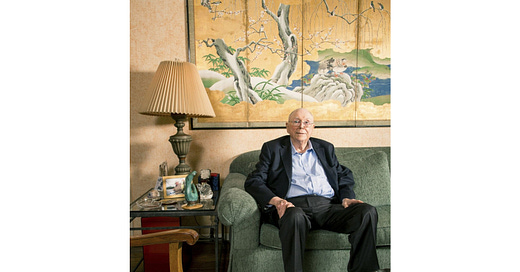

I hope to emulate his excellence in studying the character and actions of great leaders and share my learnings with you, so we can all become better leaders. This week, I’d like to discuss a favorite living person of mine, Charlie Munger.

5 Lessons from Charlie Munger

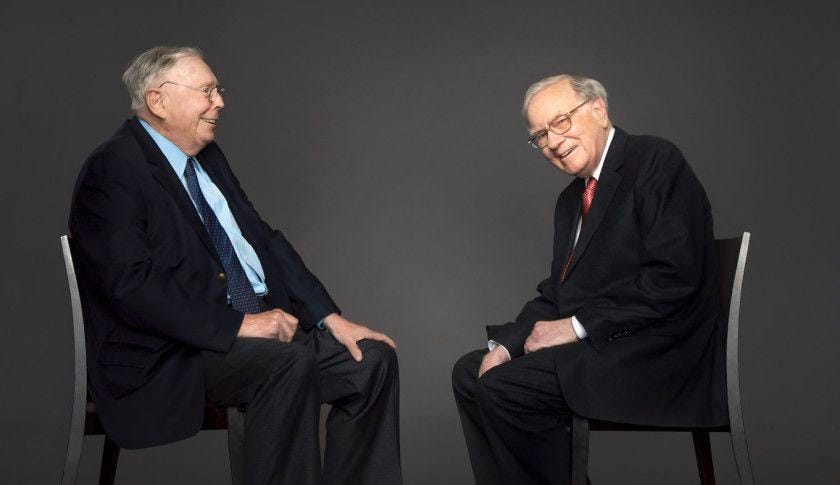

Almost everyone knows Warren Buffett, currently the third richest person in the world. But outside the field of investing, few have heard of Charlie Munger, the right hand man of Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway. Yet it is Munger, not Buffett, who has long been one of my role models in life.

Why?, you might ask. Perhaps it is because of some subtle differences between this pair of “identical twins”. Buffett is a very intense and intelligent investor, yet his entire life is centered around investing, financial statements, business books. Susceptible to hereditary diseases like diabetes, I find Buffett’s diet of soda, McDonald’s, steaks, and hash browns lethal to imitate.

Munger, however, seems more well rounded. Unlike Buffett, who purchased his first stock at age eleven and has never changed course since, Munger had studied math, meteorology, served the U.S. Army during WWII, and worked in real estate law. Though an investor through and through, Munger is more worldly and approachable to non-investors and has many less health-threatening habits that are applicable to us.

Jason Zweig and Nicole Friedman at WSJ have been busy interviewing Charlie Munger this week and wrote two high quality profiles on him:

Dinner With Charlie: The World According to Mr. Munger (short version)

Charlie Munger, Unplugged (long transcript)

In this week’s newsletter, I find the timing rather befitting to cover 5 observations on Charlie Munger that might be valuable to all of us.

1. Read, read, and read

Mark Twain once said: “The man who does not read good books has no advantage over the man who can't read them.” Munger agrees with Twain’s saying:

“In my whole life, I have known no wise people (over a broad subject matter area) who didn’t read all the time—none, zero. You'd be amazed at how much Warren reads--and at how much I read. My children laugh at me. They think I’m a book with a couple of legs sticking out.”

—Charlie Munger, Poor Charlie's Almanack

For those who have an innate drive for personal achievements while also leaving a positive impact on other people, reading is a must. Most leaders covered in this newsletter so far, such as Hamilton, Lincoln, and Churchill, are disciplined readers.

But it is important not to be “passionately interested in ideas for their own sake”, because this kind of reading leads to hedgehog thinking and make us ineffective idealists or academics like Woodrow Wilson. Instead, we should extract lessons from books that can improve our decisions as effective and pragmatic leaders. Not all great leaders are readers, but being a great reader can make a great leader.

2. Build a diverse diet for books

Reading is like eating. Instead of eating only meat, it might be healthier to include a diverse diet of vegetables, fruits, and some occasional guilty pleasures. Zweig noted Munger’s diverse diet on books:

In his study, books—Shakespeare, Twain, biographies, histories, and anthologies of humor and short stories and poetry—are everywhere. Mr. Munger says he reads himself to sleep every night, sometimes staying up until 3 a.m. (On a normal day, he’s back at his work by 8 a.m.)

Munger’s reading across history, social sciences, business, and literature isn’t merely a reflection of his immense intellectual curiosity, but also of what he calls elementary, worldly wisdom. A basic concept in his worldly wisdom is having multiple mental models:

Well, the first rule is that you’ve got to have multiple models—because if you just have one or two that you’re using, the nature of human psychology is such that you’ll torture reality so that it fits your models, or at least you’ll think it does.

And the models have to come from multiple disciplines—because all the wisdom of the world is not to be found in one little academic department.

—Charlie Munger, “A Lesson on Elementary Worldly Wisdom”

Personally, when I realized that I had been reading exclusively books on social sciences and business in the past 4 years, I began reading extensively on literature and history again. This is certainly different from the specialist approach proposed by Peter Thiel, but it has become one that I prefer for my circumstances.

3. Learn to destroy your best-loved ideas

Perhaps most relevant to aspiring entrepreneurs is Munger’s idea of being able to rationally destroy cherished ideas:

Mr. Munger: Part of the reason I’ve been a little more successful than most people is I’m good at destroying my own best-loved ideas. I knew early in life that that would be a useful knack and I’ve honed it all these years, so I’m pleased when I can destroy an idea that I’ve worked very hard on over a long period of time. And most people aren’t.

Don’t we all hate it? Just a few days ago, I received feedback on Embodied AI, the newsletter I write at work, that while my writing style is NYTimes quality, I should write a different style to make the newsletter more easily digestible. My boss, who wants to see increase in our audience, also wants to experiment with a writing style that I personally do not prefer. Though I boast the ability to take criticism very well, I confess that I spent a whole night agonizing over the critique.

Yet, you are receiving this newsletter not in my traditional longhand style of writing, but in sections broken up by bullet points. I can tell you how I persuaded myself to embrace the criticism, but Munger offers the best motivation:

Mr. Munger: I know how much power and wealth is in [destroying my best-loved ideas], so I like it. Plus that’s enlightenment. Power, wealth and enlightenment. Not a bad combination.

Hate it for sure, but the only way out is to do it until we love it.

4. Learn from other people’s mistakes

It is good to learn from our own mistakes, but it is better to learn from other people’s mistakes:

Mr. Munger: Both Warren and I feel it’s our moral duty to be as rational as we can possibly be. A lot of people who are brilliant in some ways tend to make these utterly asinine decisions in other ways. We both tend to collect the asininities of the world in a kind of checklist. And we try to avoid everything on the checklist.

Normally, we are obsessed with success stories because it feels better to hear a good story than to sit through a sad one. Success cheers us up and fills us with hope while failure deflates our motivation and alerts us of the possibility of failing ourselves. But there are two advantages to learn from other people’s mistakes and failures:

People charge you money to learn from their success stories or formulae, but failures and mistakes are usually free for grab.

Success is mostly rare and often biased, but failures are mostly abundant and often universal.

Therefore, we should turn to history to study failures diligently. It’s a treasure trove that might help us avoid expensive and painful failures at little cost.

5. Don’t lead a miserable life through your own failure of will

Despite being a billionaire and vice chairman to one of the most successful conglomerate holding companies in history, Munger is very human and down to earth. His personal life is full of obstacles and tragedies (I would love to read a high quality biography on him). For example, at age 29, Munger was divorced from his wife after eight years of marriage and lost everything to his wife, including his house.

Moreover , this divorce was compounded by the loss of his son. I also remember reading a page in Alice Schroeder’s The Snowball about Munger:

Teddy [Munger’s son] was in and out of the hospital often. Charlie would visit, hold him in his arms, then walk the streets of Pasadena, crying for his son. He found the combination of his failed marriage and his son’s terminal illness almost unbearable. The loneliness of living as a divorced single father in the 1950s also chafed at him. He felt a failure without an intact family, and wanted to live surrounded by children.

When things went wrong, Munger would set out toward new goals rather than let himself dwell on the negative. That could come across as pragmatic, or even callous, but he viewed it as keeping the horizon in sight. “You should never, when facing some unbelievable tragedy, let one tragedy increase into two or three through your failure of will,” he would later say.”

—Alice Schroeder, The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life

Munger’s left eye also went blind after a surgery. Despite all the hardship, the 95-year-old Munger is still mentally active and enthusiastic about life.

Recommendations

Should you be interested in reading more about Charlie Munger, I have two recommendations.

Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography

Franklin is Munger’s role model, and Munger recommends learning from Franklin’s autobiography more than from other biographies on Franklin. Personally, I find the Norton Critical Edition copy of his autobiography to be the most informative. (I also love Shakespeare in Norton Critical Edition)

Poor Charlie’s Almanack

Franklin wrote Poor Richard’s Almanack, and Munger, emulating his idol, penned this giant volume of Poor Charlie’s Almanack, which includes many photos, images, and excerpts to his wisdom and philosophy.

Thanks for Reading!

Make sure to click on the 💙 button to support my newsletter! Don’t forget to recommend Plutarch to your friends!