It's not the turtlenecks, silly!

3 rule of thumbs for learning leadership from history and biographies

Dear friends,

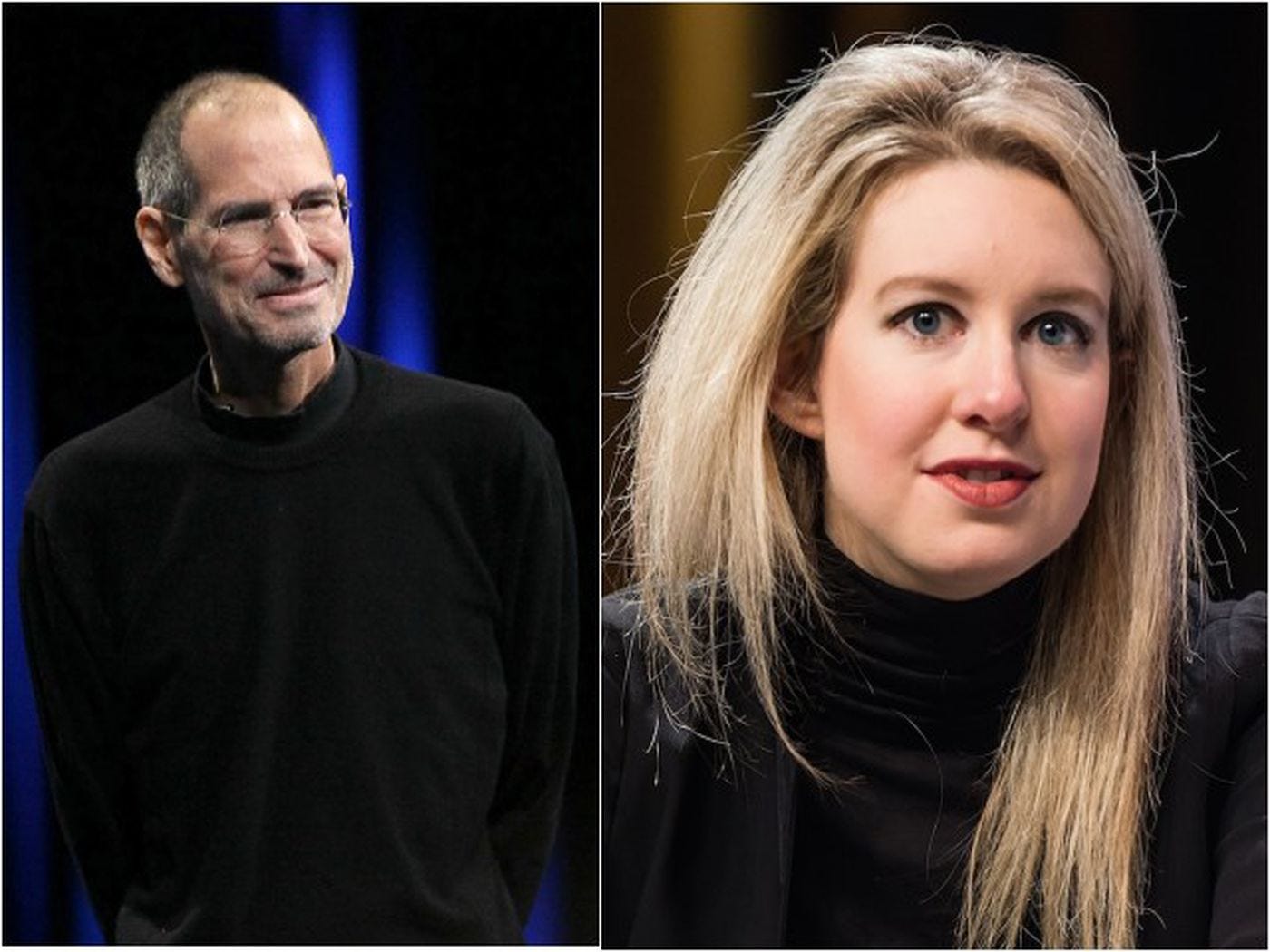

If you google either Elizabeth Holmes or the billion-dollar startup Theranos that no longer exists, chances are that the first image that pops up will display Holmes in the exact same black turtleneck that Steve Jobs used to wear. There is one passage that I remember in John Carreyrou’s Bad Blood, a vivid account of Holmes and the infamous fraud Theranos:

A month or two after [Steve] Jobs’s death, some of Greg’s colleagues in the engineering department began to notice that Elizabeth [Holmes] was borrowing behaviors and management techniques described in Walter Isaacson’s biography of the late Apple founder. They were all reading the book too and could pinpoint which chapter she was on based on which period of Jobs’s career she was impersonating.

Yet if Holmes were lucky enough to be remembered by history, it would not be as a visionary technologist who took up and furthered the mantle of Jobs; rather, it would be the frauds, hidden secrets, bad leadership, toxic company culture, and, on top of that, the death of of a renowned biochemist.

Holmes is not alone in her ambition to emulate and surpass famous leaders. Many of us learn from history, biographies, and contemporary leaders. Some admire and idolize a historical figure so much that they’d imitate the person’s eccentricities. And sometimes, like Holmes, we forget that it is not Issey Miyake’s turtleneck that made Jobs the visionary leader, but Jobs who made Miyake’s turtleneck famous.

Since we often mistake eccentricities for key traits of success, here are three rule of thumbs for how to learn from history and biographies. Comment below to let me know what you think!

1. Useful traits require meaningful efforts

If an observed characteristic does not require meaningful efforts to obtain, then it is probably irrelevant to the success of the observed person.

Lincoln’s story-telling skills did not come easily. His perpetual supply of stories that “helped many times to heal wounded feelings and mitigate disappointments” and his ability to offer “a humorous remark for nearly everyone that seeks his presence, and that but few, if any, emerge from his reception room without being strongly and favorably impressed” took an entire childhood of practices.

But a “Bezos Nutter”, a trademark of Bezos shouting at an employee with a humiliating line like “Why are you wasting my life?” (frequently found in Brad Stone’s The Everything Store) should not imply that impatience and impoliteness make a great boss. It simply means that Bezos is a flawed leader and that it does not require any effort to lose your temper and lash out at your people with verbal abuses.

Similarly, the “extraordinary” work ethics exhibited in Ashlee Vance’s Elon Musk, such as an employee’s comment that “[he]’s been working sixteen hours a day every day for years. He gets more done than eleven people working together”, might simply imply that many of these hours were spent meaninglessly. Even if Musk can work 16 hours nonstop, we mundane humans most likely will not work efficiently for long stretches of hours (Not to mention that Musk can pay the health bills which we can’t afford).

As Talent is Overrated argues, traits require meaningful, deliberate practices to develop, not meaningless hours of pretence of great work ethics or useless personality flaws.

2. Choose role models with enough exposure

Learn from people who have exposed themselves long enough in the world of randomness.

The concept behind this rule is ergodicity, which Nassim N. Taleb explained in Fooled by Randomness. The gist is that those who were unlucky in life in spite of their skills and virtues would eventually rise out of the random noises that come in their paths.

I admit that this rule is slightly biased in that it favors people who have lived a long lifespan and those who are dead already. For just like Solon’s warning to Croesus in Herodotus’ The Histories, how would we know if a person is truly a great leader until they have passed away? Moreover, this rule favors those who have either surmounted the obstacles of social mobility or have experienced many twists and setbacks that Lady Fortuna has mischievously placed in their journeys.

Therefore, my personal preference goes for those like Lincoln and Lyndon B. Johnson among the self-made men, and Catherine the Great, Elizabeth I, Theodore and Franklin Roosevelts among those among the patricians. It is not one of their achievements or one period of their lives that I judge, but rather their numerous battle-tested efforts and performance across a long lifespan. In contrast, those I have gradually learned not to enthusiastically endorse are the many who are still alive but have not yet proved their ability to shine through the course of time, such as the Silicon Valley/Seattle riches like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, and young idealists like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (We can still learn from them but should assume that their lives are still full of noises).

3. Traits only get you to the casino table

Emulating the good qualities and traits of successful leaders isn’t a guarantee of greatness, but only gets us to the casino table.

In this sense, a great trait, such as Theodore Roosevelt’s iron-like determination of self-creation or Lyndon B. Johnson’s masterful vote-counting ability, can get you to the casino and might even give you an edge in winning the Russian roulette, but they alone can never guarantee greatness. After all, Lady Fortuna has her favorite children but the caveat is that she often picks them randomly.

During the Revolutionary War, George Washington’s camp was filled with smart young officers, the most outstanding of which included Alexander Hamilton, Marquis de Lafayette, and John Laurens. These three young men, all in their early twenties, admired and loved each other for their talents and virtues. Contemporaries of theirs would assume that all three of them would have a bright future in the new republic. Except John Laurens was shot during the Battle of the Combahee River that took place just a few months before the peace agreement was signed. He died literally as one of the last casualties in an eight-year warfare. All three were hard-working, courageous, and intelligent, yet only Hamilton and Lafayette had the chance to prove their leadership later in life.

As pessimistic as it might sound, we should still try to aim for greatness. Without meaningful efforts to emulate great leaders, we will definitely not get the ticket to the casino to try out our “luck”. Fortune favors those who are prepared and if we keep trying to learn meaningful traits from other wise and great humans, at least we are very likely to improve our life quality and will not regret that we never tried.

Should this be somewhat gloomy to you, I’d recommend Charlie Munger’s saying that is both hopeful and wise:

“Spend each day trying to be a little wiser than you were when you woke up. Day by day, and at the end of the day if you live long enough-like most people, you will get out of life what you deserve.”

La Fin

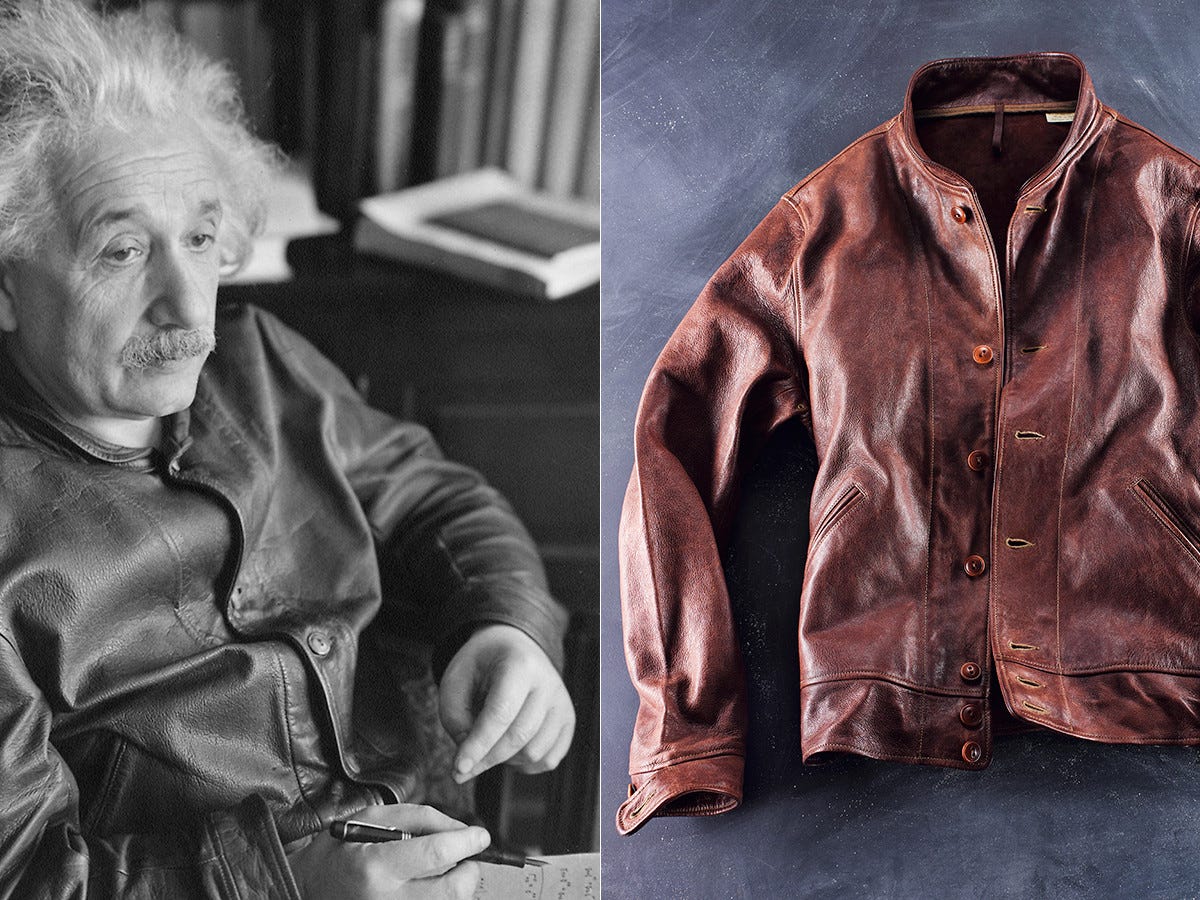

It turns out that the turtleneck episode is not alone in our culture. Last year, Levi’s reproduced the iconic Menlo Cossack jacket worn by the physicist Albert Einstein, retailing at $1,200 in limited edition. Each jacket is accompanied by a bottle of scent of Einstein’s original jacket: “a warm blend of burley pipe tobacco, papyrus manuscripts and vintage leather”. Sadly, owning one won’t make us smarter but merely creates the illusion that we share something that the great man had—an overpriced jacket.

Superfluous characters that require no effort or eccentric behaviors that live on meaningless efforts are more useless than an Einstein jacket. Even worse, they might cost you more than $1,200.

Better to stick with three rule of thumbs. Who knows, maybe Lady Fortuna will knock on your door.