5 Lessons from LBJ on Leadership

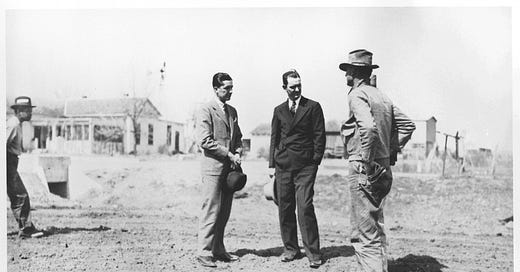

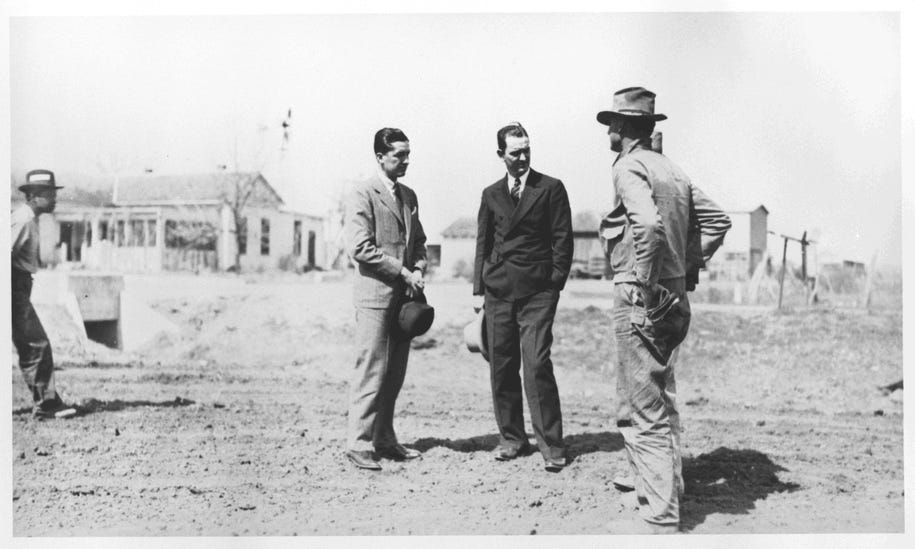

A case study from Johnson's years as the Texas State director of the National Youth Administration

If you have read my review on Robert Caro’s Working, you know that Caro’s four-volume The Years of Lyndon Johnson is on my reading list. My friend Moritz, who is ahead in reading the LBJ quadrilogy, recommended me to study Chapter 19 (“Put them to work!”) of The Path to Power, which examined LBJ’s leadership during 1935-1937 as the Texas director of the National Youth Administration (NYA).

Having read through the chapter, this week’s newsletter contains 5 lessons on young LBJ’s leadership. LBJ was a highly effective, complex, and controversial leader of his time and we will revisit Caro’s books for more studies on his character. But it is also important to remember that times have changed and so have social norms. What was outstanding leadership traits might be subjected to moral judgements today.

5 Lessons from Young LBJ on Leadership

The disastrous economic impact of the Great Depression in 1929 is unmatched by all the booms and busts in the past 90 years. Six years after the Great Depression, numerous men and women grew up lacking education and any opportunity to work. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt said “I have moments of real terror when I think we may be losing this generation.”

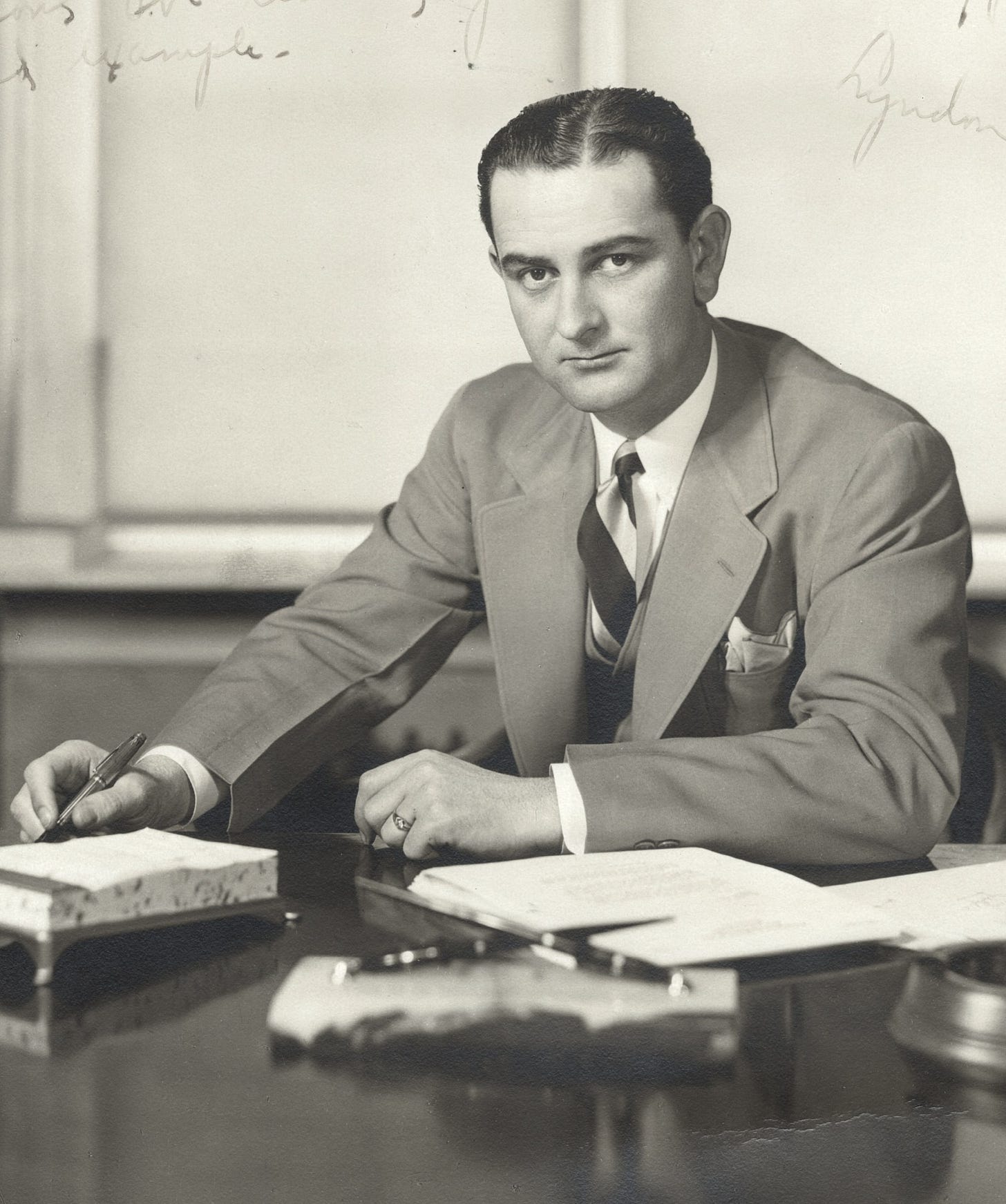

Under her initiative, the NYA was established in 1935 to educate this lost generation and put them to work. Lyndon B. Johnson, only 26 years old, became the Texas NYA director. As the youngest of the forty-eight NYA directors, Johnson was responsible for then the largest state in the USA. “Every attempt to establish a statewide public works program in Texas had been hamstrung by the variations in climatic, cultural, social and economic conditions in a state 800 miles from top to bottom, and almost 800 miles wide,” more than the combined size of 11 northeastern states.

Lyndon Johnson’s only experience with public works had been his job on a Highway Department road gang in Johnson City. Now he had to create—create out of nothing—a public works program huge in size and statewide in scope. And once it was created, he had to direct it—to manage it, to administer it. His only administrative experience was his work as Kleberg’s secretary.

Yet by the time Johnson became a congressman in 1937, the Texas NYA was seen as a successful program nationwide. How did this 26-year-old youth pulled it off?

1. Be a persuasive salesman

Among the most essential qualities of leadership, the power of persuasion ranks top. A leader needs a team of competent players who buy into the vision. The leader must be able to sell and persuade highly qualified followers to join their mission. One of the first recruits to Johnson’s team at Texas NYA, Willard Deason, recalled:

“[Johnson] was the greatest salesman I’ve ever seen. He would say, ‘Now, I’ve got a mission to do, and the money to do it with. Now you’ve got to get us a worthwhile program.’”

Despite a promising law career at a bank, Deason was persuaded by Johnson to take a 2-week vacation from his well-paid job to help out Texas NYA. During those 2 weeks, Johnson convinced him to take a 6-month leave from work, after which Deason left his job permanently for Texas NYA.

Johnson pulled off the same trick on another acquaintance, Jesse Kellam. Kellam had tasted the hardship during the Great Depression and had zero intention to leave his well-paid job as State Director of Rural Aid. But Johnson persuaded him to take a 2-week off, then another 2 weeks, and then Kellam also left his state job for this new one that paid less than half as much!

2. Build a strong (tight-knit) team

A leader could choose a highly heterogeneous or homogeneous team. Lincoln chose a team of rivals for his cabinet, wanting only the best men in the country. Managing first-rate politicians like William Seward, Salmon Chase, and Edwin Stanton, each with their personal political ambitions, was challenging and even risky. However, when managed, as in Lincoln’s case, they form a powerful force that can lead a nation out of political crises and warfares.

In contrast, Johnson demanded absolute “loyalty” in the form of unquestioning obedience from his subordinates. The type of team members he was looking for were not only willing but eager to take orders and bow to his will. Not surprisingly, his NYA team shared two traits: like himself, most of them had gone to the Southwest Texas State Normal School at San Marcos; second, most of them were in their twenties.

Johnson’s new recruits would then go through a “sifting out” phase full of long hours of work, which rid Johnson’s team of those who did not fit into his team. “The ‘sifting out’ left him with a cadre of men—perhaps forty in number—proven in his service, instruments fitted to his hand.” Johnson made those who survived feel almost like part of a family and they wanted so badly to stay on Johnson’s team.

Observers at the time noted that they seemed to like calling Johnson “Chief” and being called “son” by him. If a sycophant culture had corrupted and ruined from inside Hitler’s inner circle outward to his Third Reich, it somehow suited Johnson perfectly. Johnson had a knack for choosing his loyal followers:

“His selections—men like Kellam, Deason, Roth and Birdwell—proved, every one, to be men who were not only willing to work all day, every day, but who were also willing to take orders, and curses, without resentment; to be humiliated in front of friends and fellow workers; to see their opinions and suggestions given short shrift.”

This battle-tested, tight-knit group of Texas NYA would become a base of political power to the future Senator Johnson in the coming decades.

3. Drive (or Lead) people with energy

Those who have read Ashlee Vance’s Elon Musk or Brad Stone’s The Everything Store might be familiar with Musk’s belief that one must work 80-100 hours a week in order to change the world or how Bezos drove his employees hard at work with explosive curses. Johnson was known for his energy, quick mind, and the will to get things done. He was a workaholic. There was no work hours or weekend in team Johnson and he did not want his staff to stop working.

To control the men and to drive them to be more productive, Johnson would utilize competition to make employees work faster. He grouped them in pairs, constantly telling each one that they were slower than some other people. It was not a game that anyone could win. A staff commented that “I don’t care how hard I worked. I was always behind.” Donald Trump Jr. resembles Johnson in this respect as he is known for the same tactic, believing that it would create a winner (and a loser to be dusted out).

If Johnson drove his people hard, he also led them. Morgan recalled: “That’s the kind of assignments he’d give you—that would seem nearly impossible. But he taught you you could do them.” Caro observes that:

“Cursing his men one moment, he removed the curse the next—with hugs and with compliments, compliments which, if infrequent, were as extravagant as the curses: remarks that a man repeated to his wife that night with pride, and that he never forgot. He made them feel needed.”

4. Leverage Machiavellian manipulations

If Machiavelli’s The Prince is, with the pragmatic or even cynical statement that rulers are better off being feared than loved, the holy grail for pragmatic and cunning leaders, then Johnson is the embodiment of this Machiavellian spirit. He would curse and dominate people with cruelty. Sherman Birdwell, who knew Johnson since boyhood, said that “God, he could rip a man up and down.” According to Caro, Johnson has a “gift for finding a man’s most sensitive point was supplemented by a willingness—eagerness, almost—to hammer at that point without mercy.”

Besides fear, he also deployed gratitude as a tool. The Depression hit the entire nation hard, especially so in the Hill Country. Ernest Morgan, for example, could only earned 20 dollars a month with nine hours of work a day and six days a week. After working part-time with Lyndon Johnson, he was earning 65 dollars per month! Imagine how grateful he was. For many at Texas NYA, the gratitude was compounded with fear, as this job was the only way out for most of them. Johnson never let his team forget that he was the one who offered them the way out of their poverty.

Driven by Johnson’s desire to dominate other people, he had mastered, at 26, the art of manipulation to gave each one of his staff a “precisely measured dosage of cursing, of sarcasm, of hugging, of compliments: of exactly what was needed to keep them devoted to his aims.”

5. Inspire with vision, align your mission with their ambitions

Aside from the Machiavellian fear and gratitude he inserted into each man and woman on his team, Johnson managed to inspire people and to align their self-interest with their allegiance to him. Johnson knew how to play on their personal aspirations. “They believed that—believed that when he had better jobs to give out, they would get them.” They were all convinced that Johnson was going places and idolized him. If Johnson’s mission was successful, their ambitions would be fulfilled as well.

On top of that came a vision and a historical sense because Johnson “made them feel like part of history, too...he put them into perspective, an inspiring perspective, explaining how the NYA was trying to salvage the lives of young men and women who were walking the streets or riding the rails in despair, who were cold and hungry.” Most of his men and women found it impossible to resist Johnson’s spell and they could not be around Johnson without falling under his influence.

“First he fills himself up with knowledge, and then he pours out enthusiasm around him, and you can’t stop him. I mean, there’s no way….He just overwhelms you.”

One of Johnson’s staff, Chuck Henderson, would write to his fiancé, Mary, that “I’m working for the greatest guy in the world. Someday he’s going to be President of the United States. And he’s only twenty-seven years old!”

Verdict: a Reader of Men, a Master of Men

The NYA was a political exercise that allowed Johnson to bring people together under his leadership so that he could observe and test them, assessing not only their personalities but their potentialities. It also served as a political machine that would later help Johnson control Texas.

If contemporaries were somewhat disgusted by LBJ’s manipulative traits, his contemporaries had better things to say. Mary Henderson’s memories of Johnson serves as a powerful summary of his leadership during 1935-1837 at Texas NYA:

“But he had what they call now a charisma. He was dynamic, and he had this piercing look, and he knew exactly where he was going, and what he was going to do next, and he had you sold down the river on whatever he was telling you. And you had no doubts that he was going to do what he said—no doubts at all. You never thought of him being only twenty-seven years old. You thought of him like a big figure in history. You felt the power. If he’d pat you on the back, you’d feel so honored. People worked so hard for him because you absolutely adored him. You loved him.”

Leadership has been and will always be a tricky business. Leaders have different upbringings and motivations for power, and followers have their own ambitions and agenda. To make a group of people work and change things, there will always be truthful persuasions bordering on blatant lies, sincere intentions mixed with Machiavellian manipulations, the struggle to balance a meritocratic team and the vane human desire for sycophantic praises, and confusing self-driven work with abusive labor exploitation. These tensions are especially pronounced in Caro’s study of LBJ.

It is important for us to keep other contemporary or historical leaders in mind when studying LBJ’s leadership. In Chinese, there is a saying “八仙过海, 各显神通,” which, after losing all its original beauty, roughly translates into that we each have our unique advantages and specialties on our path to greatness. Some of LBJ’s greatest skills were secrets, lies, manipulations, and a fox-like ease to switch side. But many of us would not wish to lead like LBJ. Luckily we don’t necessarily have to.

LBJ has much to offer in our pursuit of great leadership. Some we must learn to excel. Others we must learn to eschew.